Welcome back to WHR Radio Where You Decide!

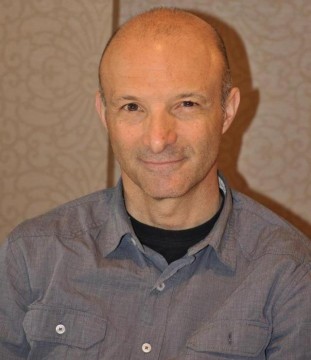

We are pleased to announce our next special guest host, Frank Cassini, who will join WHR Sunday July 1, 2012 5 PM Pacific, 8 PM Eastern time to discuss his human interest topic, “Teaching Acting”. As always, we will do a full post interview follow-up news article featuring Frank Cassini.

The Challenges and Rewards of Teaching:

If you have ever been responsible for children, participated in a workshop, or trained a new employee, you have engaged in some form of teaching. The collaborative act of teaching and learning has been part of our social structure as a civilization for as long as we have connected to each other.

From our early history, we have engaged in helping one another through teaching. Early humans taught each other how to hunt, then how to farm. When we began bartering for goods that we created, we taught by apprenticeships.

A young person would be sent away to work and study under an artisan; a craftsman who worked with stone, for example, to create buildings, or a baker who made bread. Once the apprentice knew everything that the artisan could teach, the apprentice became the master stone cutter, baker, or whatever was required to maintain the community.

Now, things have gotten much more complicated. Now, we expect those who teach to have higher education. After all, teaching is serious business. Teachers mold the young minds of the people who, in a few short years, will be taking their place as our financial and political leaders.

However, there are other learning experiences. Have you ever taken a pottery class, or a class in abstract art? Have you wanted to learn how to play tennis, or golf? Are you curious about astronomy or believe that tarot card reading is a useful skill? Do you want to learn more about history or improve your ability to speak French? Chances are that these learning experiences were much more fun than anything you learned in high school.

As social beings, it is natural for us to want to learn. Learning helps us to survive as a species. We need to develop skills that create an environment where we are less likely to become another creature’s lunch. It is also more productive for our need to reproduce. The most successful family is the one with the greatest skill set.

As social beings, it is natural for us to want to learn. Learning helps us to survive as a species. We need to develop skills that create an environment where we are less likely to become another creature’s lunch. It is also more productive for our need to reproduce. The most successful family is the one with the greatest skill set.

As Peter Gray, Ph.D., a research professor of psychology at Boston College states, “skill development, especially in mammals, often requires a great deal of practice. Young mammals come into the world highly motivated to practice the skills they need to survive, but in some cases they are unable, by themselves, to create the conditions necessary for practice. In these cases, teaching may occur simply by providing those conditions”.

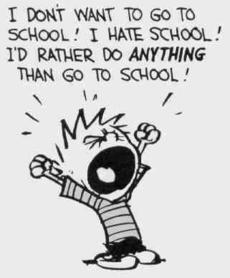

So, why do we seek out educational opportunities as adults that we shun as children? What has changed? Maybe it is how children are taught that is the root of the problem. After all, children do not start out hating school or hating learning. But, as time passes and they graduate from one grade to another, they begin to really hate attending school.

Children explore and play, freely, in ways designed to learn about the physical and social world in which they are developing. In school they are  told they must stop following their interests and, instead, do just what the teacher is telling them they must do. That is why they do not like school.

told they must stop following their interests and, instead, do just what the teacher is telling them they must do. That is why they do not like school.

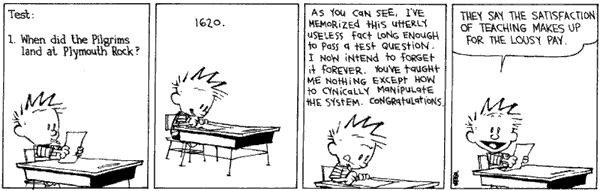

As a society we could, perhaps, rationalize forcing children to go to school if we could prove that they need this particular kind of prison in order to gain the skills and knowledge necessary to become good citizens, to be happy in adulthood, and to get good jobs. Many people, perhaps most people, think this has been proven, because the educational establishment talks about it as if it has. But, in truth, it has not been proven at all.

Every new generation of parents and every new batch of fresh and eager teachers, hears or reads about some “new theory” from psychology that, at long last, will make schools more fun and improve learning. But none of it has worked. And none of it will until people face the truth: Children hate school because in school they are not free. Sitting at a desk and listening to a droning adult is not natural for children. Joyful learning requires freedom.

Learning can be fun. We all know that. If we are engaged in an activity that we enjoy, the learning comes as a natural and pleasant by product. It does not need to stop there. When we have mastered a skill, continuing to practice that skill, especially if we enjoy it, does not feel much like work. Do you recall hearing a sports figure claim that they would be happy to, “play for free”, but the money is still welcome?

One of the first and most often reinforced lessons that children learn in school is that work and play are opposites. Work is what one has to do; play is what one wants to do. Work is often unpleasant; play is fun. Work is essential; play is trivial. But when we leave school and go on to the “real world,” at least some of us, the lucky ones, discover that work is not the opposite of play. In fact, work can be play, or at least it can be imbued with a high degree of playfulness.

One of the first and most often reinforced lessons that children learn in school is that work and play are opposites. Work is what one has to do; play is what one wants to do. Work is often unpleasant; play is fun. Work is essential; play is trivial. But when we leave school and go on to the “real world,” at least some of us, the lucky ones, discover that work is not the opposite of play. In fact, work can be play, or at least it can be imbued with a high degree of playfulness.

Play is what we choose to do, not what we have to do, so the more we experience a sense of choice about our employment the more we experience it as play. If you feel that necessity requires you to work at such-and-such a job, then it will be hard for you to maintain a playful attitude about that job.

Play is what we choose to do, not what we have to do, so the more we experience a sense of choice about our employment the more we experience it as play. If you feel that necessity requires you to work at such-and-such a job, then it will be hard for you to maintain a playful attitude about that job.

The more you feel free to leave a job, the easier it is to experience the job as play. Play, by definition, is something that you are always free to quit. If you can’t quit, you have no sense of choice, and the activity is not play.

The broader point here is that, regardless of the kind of work we do, the more we can adopt the attitude that we don’t really have to do this work, the more we can experience the work as play. Slavery is outlawed now, so at least in theory all of us should have the opportunity to choose the work by which we earn our income, though I recognize that economic conditions can sometimes make this difficult.

Schoolchildren, of course, experience no freedom about being in school or not. They are required by law to be there. That is one reason why schoolchildren rarely experience their schoolwork as play. We do not, in our society, provide the same basic freedoms for children that we do for adults.

Sociologist Melvin Kohn of Johns Hopkins University, and his colleagues identified a highly desired constellation of job characteristics that they referred to as occupational self-direction. Jobs high in this quality are those that are complex rather than simple, varied rather than routine, and not closely supervised by  others. Micro-managers need not apply.

others. Micro-managers need not apply.

Kohn and his associates discovered that workers who went from a job low in occupational self-direction to one high in that quality not only experienced more pleasure at work but also changed psychologically over time. They became more flexible, less rigid, in their home life and hobbies as well as in their work life. Their parenting styles became more democratic, less autocratic. They began to value creativity and autonomy in their children above blind obedience. In other words, their whole outlook toward life became more playful than it was before.

Play is an activity that is done for fun rather than for some end that it produces. Play may have ends, but it is the process of achieving the ends, not the ends themselves, that is most valued. It is the creation of the sandcastle, not the sandcastle once created, that players on the beach enjoy. It is the process of scoring points or trying to score them, not the points once scored, that pleases tennis players, if they are truly playing. In other words, in play the activities themselves are the source of pleasure; any product that may emerge is a side effect.

Thus, play which is a very effective form of learning, works best when it occurs freely and is of interest to the person involved. If we want children to stop hating school, we need to refocus on the way they learn. Any form of education should not be a prison. Let’s look for new ways to unlock the cage.

Thanks to Kenn for final staging of the audio and images in this news article and thanks to you for stopping by WormholeRiders News Agency! We look forward to seeing you for our exclusive interview with Frank Cassini this Sunday 5 PM PST 8 PM EST!

Thanks to Kenn for final staging of the audio and images in this news article and thanks to you for stopping by WormholeRiders News Agency! We look forward to seeing you for our exclusive interview with Frank Cassini this Sunday 5 PM PST 8 PM EST!

Please feel free to leave a comment here, click an icon below to share this interview with your friends, or you can visit and follow me on Twitter by clicking on my avatar to the right.

Regards,

Thank you.

ArcticGoddess1 (Patricia)

There’s a balancing point between basic instruction and play. The ugly truth is some of us hate certain subjects. We. Just.

Don’t. Like. Them. You can dress up division however you like, but I say it’s succotash and I say to hell with it… and at a certain point, I had to learn how to do it.

That being said, there’s a need for more investigation, more hands-on materials, more discovery, etc. in teaching. I teach in the Independent Learning Center, and I work with kids who are on opposite ends of the learning spectrum, generally – the accelerated kids and the kids who struggle. Sometimes kids come in for a one time extra help session, or because they were out sick or are having a test-anxiety seizure of sorts. But for about ten years, I was a high school or middle school English teacher. I’d like to be a general elementary teacher, integrating all the subjects – that would be challenging but extremely fun. I’ve taught all over by now – in rural Maine, working class suburban Philly, alternative ed (and not the granola sort) high school, just outside of Detroit, and working class mostly white high school, just outside of Detroit. I moved a lot because my husband was going to grad school and then was a roving academic; now that he has tenure at the U of Michigan, I may well stay in my small parochial school in Ann Arbor. We take in a number of scholarship kids, and I still work with some academically at risk kids, too – this is no country club school. It’s great to think “Let the children play” but also – as Henry Wong puts it in The First Days of School (he exaggerates but has a point), school is their version of work, essentially. I love my “work” – teaching, and I aim to help them enjoy their “work” – and most kids love the ILC. They don’t want to leave. But they do know they also must work hard, think hard, do quality work – they enjoy the learning, the payoff. They’ve learned that this feels good, ultimately – and it’s a new experience for many of them. We can teach that, too – pride in accomplishment. You don’t get that, playing around.